This is the second of the three anniversaries the Woodstock Folk Festival is commemorating this year. See here for background on Earth Day (April 22). And stay tuned for information about the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the U.S. (August 18-26).

Music played an important role in all three movements as shown in our April 5 concert and bibliography (still available on this site) as well as in the music selections mentioned later in this article.

This article was written by Carol Obertubbesing, President of the Festival, a trained historian, and a participant in the Student Strike of 1970.

NOTE ON EVENTS

WDCB’s Folk Festival show hosted by Lilli Kuzma will feature a special segment on the 50th Anniversary of Kent State and Jackson State on Tuesday night, May 5, between 8-11 p.m./CDT. Tune in to 90.9FM or wdcb.org. There will be virtual commemoration events at Kent State on May 4, 2020. Visit www.kent.edu for details. Jackson State also scheduled commemorative events and an exhibition. Details are at mshumanities.org.

BACKGROUND

The Student Strike began on May 1, 1970, the day after President Richard Nixon announced the invasion of Cambodia. Strike groups sprang up overnight on campuses across the country. At its peak, students at over 700 college, university, and high school campuses joined the strike.

On May 4, National Guardsmen killed 4 student protesters and injured more on the campus of Kent State; on May 15, 2 students were killed and others injured when police confronted students at Jackson State College in Mississippi. The Scranton Commission, appointed by President Nixon to study unrest on college campuses, later found the shootings at Kent State – over 60 shots by Guardsmen – and Jackson State – 460 shots by police in Jackson – to be “unjustified.” Both universities now have memorials honoring the victims. Sadly, many accounts of the anti-war movement mention only Kent State even though at the time we spoke of both events.

In the ensuing weeks hundreds of thousands of students gathered in Washington and other cities across the country to protest the War, often shutting down ROTC offices on campuses. In some ways it was a culmination of a decade of change, activism, and growing disillusionment with and protests against the war in Vietnam (or as the Vietnamese now call it “The Resistance War Against America” or “The American War”).

The 1960s began with the election of America’s youngest (elected) president, John F. Kennedy. His words, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country,” fueled a decade of activism.

In a May 1961 address, Kennedy challenged the nation to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. He didn’t live to see that happen but it did happen on July 20-21, 1969. Exploration of space fired people’s imaginations and made many people, particularly young people, feel that anything was possible. It was a time of great hope and optimism. The Voting Rights Acts and President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs helped people attain things they had not had before. With Vatican II, the Catholic Church was changing and there was a growing ecumenism. Books such as The Man inspired people to talk about issues previously beneath the surface. New teaching methods were implemented. Women’s rights and gay rights began to be discussed and even reached pop culture. There were new directions in literature, music, art, dance, and theater. Experimentation became the norm rather than the exception.

Yet there was a dark undercurrent as well. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963; Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in April 1968; and Senator Robert F. Kennedy, in June 1968. Cities experienced turmoil and riots broke out across the country – from Newark to Detroit to Watts. Students began to protest – demonstrations at Columbia University in NY; University of Wisconsin in Madison; and then in 1970 all over the country. Large scale demonstrations such as the 1963 March on Washington in which Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his “I Have a Dream Dream” speech and draft card burnings turned the attention of the nation to issues of civil rights, social justice, and the growing peace movement. Sometimes families were torn apart because of opposing opinions. We were an angry nation as well as a nation of dreamers.

Against this backdrop came the Student Strike of 1970.

A PERSONAL ACCOUNT OF THE STUDENT STRIKE OF 1970

In September 1969, I stepped onto campus as a member of the first coed freshmen class in Princeton University’s history. Princeton is one of the most idyllic campuses. There are many beautiful gothic buildings interspersed among quadrangles where students played frisbee, and “In A Gadda Da Vida” blasted from open dorm windows on warm days. The sweet scent of magnolias was in the air. Whig Hall which burned in the fall was being repaired and a construction wall had painted images such as a sun rising in the morning. It was a time of discovery and new horizons but never more so than for a freshman girl who had grown up in the most densely populated city in the country and arrived at this storied university.

I had been a supporter of the Vietnam War in early ’68 but by later that year, after seeing violence against students on the Columbia campus and violence against demonstrators at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, and after reading about teach-ins on the war, I had changed my mind. Yet as I struggled socially, academically, and financially in 1969-1970, politics was not uppermost in my mind. However, when President Nixon, who had pledged to end the war during his 1968 campaign, expanded the war by invading Cambodia, my interest in politics and in effecting change was reawakened. Classes were cancelled or discussions turned to current events. Many members of the Class of 1970 traded caps and gowns for black armbands, some with the peace symbol.

While Princeton had campus demonstrations, particularly at the nearby Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA), it had avoided the extreme violence that some campuses had seen. President Robert Goheen encouraged an atmosphere of dialogue so when the strike began, there was a convocation of the campus community – administrators, faculty, staff, and students — at Jadwin Gym. Three major groups formed on the Princeton campus.

The first, the Student Strike Committee, was, at least in my mind, the most radical; they wanted change on many fronts, not just the war. I felt that they had such a broad agenda that they would spread themselves too thin and not be able to accomplish any specific goals.

Another committee was the Movement for a New Congress which sought to effect change through the electoral process. If we elected different representatives, we could change the nation’s course. The fall break at Princeton, where students could return to their hometowns to work for candidates for a week before the election (and some vote themselves), was the result of this. At the time, students felt disenfranchised. Young men could be drafted at 18 but couldn’t vote until they were 21. Since elections usually came during the semester, many students couldn’t return home and because their dorm address wasn’t considered a permanent address, they couldn’t vote where they went to school. Movement for a New Congress sought to change that.

The third organization founded on the Princeton campus was the Union for National Draft Opposition (UNDO). This organization, in my mind, had a specific and more achievable goal. Since many boys in my public high school didn’t go on to college and were subject to the draft, I saw a disparity and injustice. If they did object to going to war (for political, moral, or religious reasons), they often would not know where to get help. By pamphleting draft boards, speaking at schools, and providing counseling, I believed we could help them. More radical leaders in this movement included Father Philip Berrigan, his brother Father Daniel Berrigan, and other members of the Catonsville Nine as well as the Chicago Seven. There were some violent incidents during the anti-war demonstrations and draft protests, but most were peaceful.

There have been drafts throughout American history, but the 1940-1973 draft began with the Selective Training and Service Act and was the country’s first peacetime draft. Between 1964 and 1973, the U.S. military drafted over 2 million American men. Thousands of men, including the late singer-songwriter Jesse Winchester, fled the country, many to Canada. The lottery established in 1969 strengthened the anti-war movement. The draft ended in 1973.

The University gave us office space in Palmer Hall and we immediately began to set up an office – everything from learning how to set up a postage meter for bulk mailings to giving talks to the community to traveling to Washington for demonstrations to setting up chapters at colleges and university across the country. From schools such as Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, NY to the University of Oregon in Eugene, OR, we communicated, by phone and mail (no internet or email nor cellphones in those days), with colleagues across the country. Occasionally we sent speakers and organizers to those other colleges. I met community members from organizations such as the American Friends Service Committee, the War Resisters League, and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. The walls between the University and the community were coming down. As a symbol of that, the University’s Fitzrandolph Gate was opened and has stayed open ever since.

It was a “heady” time — yes, for some people that meant smoking grass and taking drugs — but for others such as myself, it was a time of learning, of new ideas, of new paradigms. My mind was exploding. I remember long rap sessions at night talking about politics, music, books, poetry – and almost any other topic under the sun. Living with a group of 10 people in a house we rented near the campus so we could continue to work during the summer was my first experience of living outside my family home. I feared my father, a World War II veteran, would disown me but he didn’t. I realized later that for some people who fought in wars, they fought for a cause, but they didn’t want to see any more war. I did have friends who were disowned by their parents – some lost all financial as well as emotional support.

As I was living this important part of American history, my personal history was changing too. I met another UNDO staff member, Mike Epstein, then a junior at Princeton. On June 10 there were major demonstrations around the country, I demonstrated outside the draft board in Trentons, NJ; Mike went to Washington, where he was held up at knifepoint while sleeping with hundreds of others in a church.

In late June the organization needed two people to go to Milwaukee for a conference featuring David Dellinger. We stayed in the home of faculty members – this is long before the days of Air bnb. That trip was the beginning of a relationship that lasted over 40 years. Years later when Dave Dellinger spoke at the Chicago History Museum, we went to hear his talk and afterwards told him that our marriage was an unintended consequence of the Student Strike. We all laughed and he had some kind words for us. I recommend reading his book, From Yale to Jail.

After the conference we hitchhiked to Madison to visit some of Mike’s friends who took us to my first folk concert. People were sitting all around one of the lakes singing songs of peace, love, and freedom. My love of folk music began at that moment.

Popular slogans included “Hell No I Won’t Go” and “Just Say No” (a friend has a famous poster that says, “Girls Say Yes to Boys Who Say No”).

That summer we’d spend nights working in the office — I, preparing documents and handling mailings – he, learning to play guitar in between his projects. He taught me the music of Phil Ochs, Joan Baez, Tom Paxton, Judy Collins, and Bob Dylan. In the mornings, we would get up at 4 to protest at the draft board in Newark. With our roommates at the house, we’d listen to music from Cream to Jacques Brel; we’d share poems with each other; we’d stay up into the wee hours of the morning talking about politics and life. It was a time of finding the energy to do things we might otherwise have thought impossible.

When histories of the 60s are written, they often focus on “drugs, sex, and rock and roll” or “flower power.” They usually fail to capture the tremendous optimism of the 60s – the sense that “yes, we can change the world.” Perhaps that’s why Barack Obama’s campaign slogan “Yes We Can” resonated with many of us “baby boomers.” It was also a time when young people came together, put their energy and hearts into these issues, and worked tirelessly – at least for a few years — to achieve these lofty goals. What did we achieve?

LEGACY

The draft ended in 1973.

The voting age was changed from 21 to 18. If young people were asked to go to war, shouldn’t they have a say in the people who made those decisions? The 26th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, giving citizens 18 years of age or older the right to vote, was ratified in July 1, 1971, just a little over a year from the time the Student Strike began, the fastest time an amendment to the Constitution had been ratified.

Rules changes opened up the political conventions.

Issues beginning to be discussed in the 60s came to the forefront and both laws and attitudes have changed as a result of that. Women’s rights, LGBTQ rights, environmentalism (everything from organic farming to vegetarianism to climate change), concerns about fitness and health, and social justice issues, received more attention in the years since 1970.

THE ROLE OF MUSIC

Music brought people together – it’s hard to sit in a song circle and hate the person sitting across from you. It highlighted the issues, provoked thought, moved us to actions — sometimes in a serious way such as Barry McGuire’s “Eve of Destruction” or Phil Ochs’ “I Ain’t Marching Anymore,” sometimes in a more humorous way such as Phil Ochs’ “Draft Dodger Rag,” sometimes in provocative songs such as “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” and other times in beautiful songs such as “Get Together.” I encourage you to listen to these songs as well as the following to try to capture the thought and spirit of the time.

- “Ohio” by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young – written by Neil Young in reaction to the Kent State shootings

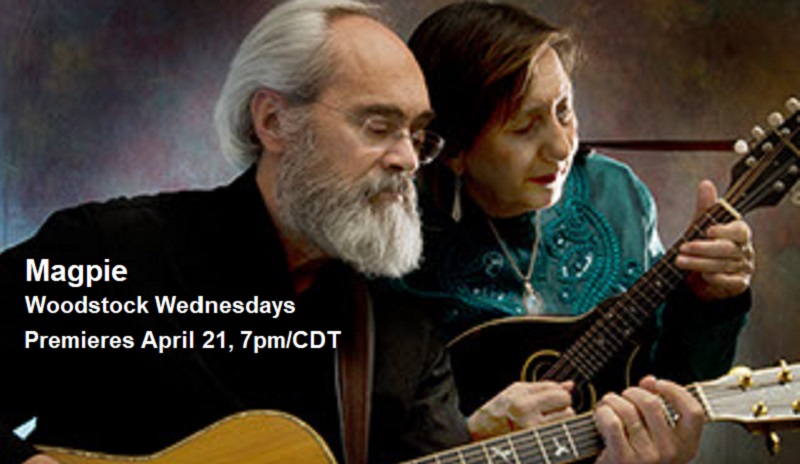

- “Kent” by Magpie (the duo of Terry Leonino and Greg Artzner) on their album Give Light; Terry Leonino is a survivor of the Kent State shootings

- Dave Brubeck’s cantata “Truth is Fallen” was dedicated to the slain students of Kent State and Jackson State and other innocent victims

- Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?”

- Steve Miller’s “Jackson-Kent Blues”

- Bruce Springsteen’s “Where Was Jesus in Ohio?”

- Barbara Dane’s “The Kent State Massacre”

- “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin-to-Die” by Country Joe and the Fish

- “For What It’s Worth” by Buffalo Springfield

- “Fortunate Son” by Creedence Clearwater Revival

- “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around” by Joan Baez

- “The Universal Soldier” by Buffy Sainte-Marie (also a hit for Donovan)

- “Bring ‘Em Home” by Pete Seeger

- “Give Peace a Chance” by John Lennon

- “Masters of War” and “Blowin’ in the Wind” by Bob Dylan

- “War” by Edwin Starr

OTHER RESOURCES

You may also wish to check out:

- The Cost of Freedom: Voicing a Movement after Kent State 1970, an anthology that includes poetry, personal narratives, photographs, songs, and testimonies, some written by eyewitnesses to the day of the shootings.

- The 1981 movie Kent State focused on the four students who were killed.

- In 2000, Kent State: The Day the War Came Home, a documentary featuring interviews with injured students, eyewitnesses, guardsmen, and relatives of students killed at Kent State, was released.

CONCLUDING THOUGHT

For most of us – no matter what generation – there is a soundtrack to our lives, but perhaps there was never a time when that soundtrack was so inextricably mixed with the burning issues of that time.

![Meghan Cary video image july 2020[7293]](https://woodstockfolkfestival.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Meghan-Cary-video-image-july-20207293.jpg)

Great job, Carol. You really captured the essence of those times.